(Paru dans le National Post, le 17 janvier 2006)

The type of support promised for childcare services is one of the issues that has defined the three principal political parties during this federal election. Stephen Harper's Conservatives have promised approximately $1,200 per year to families for each child under 6 years of age; the Liberals have promised a national early learning and childcare initiative based on the Quebec model of subsidized childcare; and the NDP have promised a Child Care Act that would reserve federal funds for licensed, high-quality, non-profit childcare centres.

Those who support the Liberals' national program cite the example of the childcare centres set up in Quebec after the quasi-nationalization of day care in 1997. Canadians have been led to believe that the Parti Quebecois (PQ) provincial government in power at the time had found the right formula and that all parents have access to a quality service at the affordable price of $7 per day. However, the situation in Quebec is not nearly as rosy.

The Quebec childcare reform decreased outlays for parents from about $25-30 per day to $7, effectively eliminating cash-flow issues for lower-income families. But the drop in price increased demand and resulted in a shortage of spaces (given the government's limited budget capacity), as well as waiting lists of up to 2 years for subsidized spaces. While waiting, parents who need childcare continue to pay the market price. This has effectively created a system where access to a subsidized space depends neither on parents' financial circumstances, nor on the needs of children who may require special help to prevent learning difficulties later. The only factor that now plays a role is the rank of a child on a waiting list, i.e., bureaucratic convenience.

The way funding is channeled to these childcare centres explains many of the shortcomings of the 1997 reform. Quebec shifted from a system that helped parents buy childcare services to a system of subsidies to the providers of those services. The PQ government limited the purview of childcare centre administrators and began setting the pay of childcare workers. So the salary demands of those workers were then directed to the public treasury rather than to the childcare centre administrators. The negotiation of sector-wide collective agreements has led to strikes, which have caused the loss of 73,000 person-days of work since 1997, more than double the 34,000 person-days lost between 1990 and 1997.

In addition to fostering labour disputes, this system of funding providers instead of parents has also limited parental choice. The childcare centres certainly meet the needs of many parents. But with the growth of freelancing, telework, and sporadic and part-time work, an increasing number of parents are looking for flexible options that these childcare centres are hard-pressed or unwilling to provide.

Several surveys have shown that many Canadian parents prefer to care for their children themselves. Among specialists in early childhood development, some advocate early socialization in group childcare venues, some favour parental care at home at least for children who do not face any specific challenge. Yet all forms of support for childcare by a third party ignore the needs of parents who choose parental home care, for reasons related to their values or their individual economic circumstances.

How can we better acknowledge the range of parental preferences? What would reduce the potential for labour disputes in publicly funded childcare centres? The key is in the allocation of public funds for childcare among the different types of support. If the government simply wants to redistribute wealth to families, cash transfers and tax rebates suffice; there is no need to fund childcare specifically. If government wants to increase the labour supply, then it can help parents purchase childcare services without any restriction as to the type of services provided. If government believes that early socialization is beneficial for children, then it can help parents buy childcare services in centres that have appropriate early learning programs. But none of these policy objectives requires channeling funds directly to childcare service providers.

When purchasing power remains in the hands of those who benefit from a service, providers remain responsive to user needs. When funding for that same service comes from a central authority, conformity to norms often takes precedence.

In the end, there are several good reasons to empower parents through cash transfers, vouchers, or tax rebates for childcare rather than directly subsidizing childcare service providers.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Politique publique | Public policy

Bienvenue sur mon blogue !

Vous trouverez ici des réflexions sur des questions de politique publique. Pour entrevue média, svp me contacter par courriel: pdm@pauldanielmuller.com

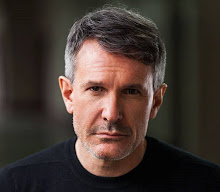

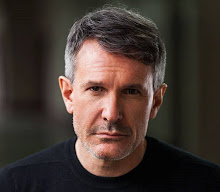

Bio

- Paul Daniel Müller

- Économiste de formation, praticien des affaires publiques, j'ai travaillé pendant 30 ans à concevoir, influencer, promouvoir, implanter et évaluer des politiques publiques. J'ai exercé mon métier au gouvernement, auprès de deux partis politiques, comme consultant auprès d'entreprises et d'associations sectorielles, ainsi que dans un think tank.

Politique

Libellés | Tags

- Administration publique (15)

- Agriculture (4)

- Éducation (6)

- Énergie (4)

- Environnement (2)

- Famille (3)

- Finances publiques (33)

- Fiscalité (23)

- Forêts (2)

- Immigration (2)

- Industrie et commerce (18)

- Intergénérationnel (11)

- Kultur (2)

- Main-d'oeuvre (6)

- Municipal (7)

- Politique (11)

- Régions (8)

- Réglementation (8)

- Santé (4)

- Sécurité (1)

- Transport (4)

- Travail (7)